One little boy lifted the silver bowl of chicken heads to receive its next occupant, and I snapped out of my time-traveling thoughts. I stood up and returned to Vita's house to find that the iPad had locked away its contents from the curious kids indoors. When I unlocked the iPad, I found the following paragraph, scribed by Samu:

Washing away old worries in a stone cathedral

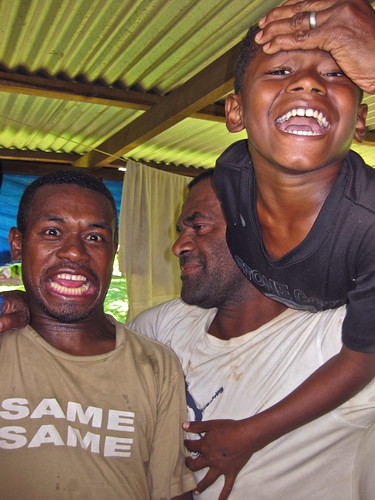

“This is for you, Lindsay.” Waisale stood at the top of one rock wall, arms folded, and stepped forward into the air. I photographed his rapid descent and felt my stomach uncurl of worry. Before, I feared that suddenly departing their lives without explanation would sever ties or permanently damage our connection to the kids. These fears dissolved by the time Waisale resurfaced from the bottom of the gorge.

An emotional, highly anticipated return to Nakavika

Returning to my first lemon leaf tea in five years, I happily settled on the grass mat with a Christmas mug. I was nearly out of the emotional woods with this favorite, sweet elixir and a few cold pancakes. I sighed and scanned the room, finally noticing two photos taped to the wall, one of my mother in the snow and another of my grandmother holding my baby niece. I should have just accepted that a breakdown was inevitable.

Reunited with the Fiji of my dreams in the markets of Suva

I reacted in amazement before the information reached my brain: Siteri was standing in front of me...at the market in Suva...spotted me the moment I arrived with no other knowledge than my flight time. I guess I could have anticipated this crossing of paths in retrospect, because we had been connecting on Facebook, little blue lines coming onto my screen from a dream I once had. Regardless of the plausibility of the chance encounter, I was now face-to-face with tangible evidence of my long and confusing stint in Fiji, a time I still chew on in my mind for more clarity and takeaways. Her name is Siteri, and she is my umbilical cord to Nakavika.

Back to being just a tourist: Day 74

Gasping for relief and peace after leaving all of Nakavika in my wake, I finally turned to my taxi driver, a middle-aged, toothless Indo-Fijian with a cheeky grin ready to start some chit-chat. Once again, I had a conversation with a local that scored me points for America in their eyes, and knowing the consequences of getting too invested and connected, I refrained from supplying him with my phone number, which he requested. I remained kind but cold, occasionally hyperventilating from a hard cry long gone. It was a sunny day on the Coral Coast. I made my way to The Uprising and straight to the bar.

Standing on shipwrecks and witnessing another: Day 69

Tears spewed out of everyone's eyes, some came twice to say heartfelt goodbyes, and Abel was left standing on the sidewalk crying, watching my taxi pull away. Our project represented a lot for him, but unfortunately the collaboration couldn't be as we all wanted it to be. Instead we implored him to do what he felt was right, to continue helping the children by leading by example. While I watched him in the side mirror growing smaller, it was evident he didn't believe he could be the man he wanted to be without a little help from those who expected his best.

Instant withdrawal from the kids: Day 63

One side of the sky was navy blue and brilliant with stars and a succulent moon; the other side hinted at the curvature of the globe with shades of pink. The dew making my feet squeak in my flip-flops mirrored the moisture on my eyelids. There wasn't a wavering thought in our minds about returning to the village, so this morning absolutely marked an end. Knocking on a few doors at dawn, we came across the home where little Weiss was sleeping. It would have been impossible to take our final carrier ride without saying goodbye to our dear friend and favored student of 2.5 months. We hugged him and asked him to tell the other kids we say goodbye and will miss them. He nodded his heavy head, instantly taking the form of an older, mature being with wise eyes that see the realities of a world he can't change.

The sweet sorrow of departing: Day 62

I opened my eyes as if they'd been closed for only a few seconds. Stains decorated the holey mosquito net, which now ensnared a circling bunch of blood-filled bugs. Though I've never been physically beaten up, I imagine the next morning would have felt akin to how I felt there, in that bed, feeling the bed springs scratch my skin, every muscle upset and tense from a terrible day prior.

I don't feel good here anymore.

The hell-raising fundraiser: Day 61

Imagine the clamor of a crowded gym at a small town regional basketball tournament, thousands of feet stomping the bleachers causing the air to vibrate. Imagine Black Friday crowds shivering outside Walmart at 4:59am, eyeballing the unfortunate fellow about to rip open the doors for the stampede. Imagine wanting so badly for someone to hear your message, a message that would clarify a seemingly sketchy concept into that of a laudable and worthwhile endeavor. This was the energy of our fundraiser.

The first and last school visit: Day 59

Last I left the tales of this Fijian adventure, there was a major event that happened - one which led us to doubt the possibility of our project coming to be. After issues were resolved (in the eyes of the elders), we asked the Turaga ni Koro (village spokesman) to hook us up with a ride down to the coast for a few days. We needed some space to figure out what to do.

The danger of not processing the bad: Day 55

We all shake our heads at the shoulder-patting, "aww gee"-inspiring cliches from the psychology world, but there's no doubt they come from a necessary concept. When the traumatic, the all-of-a-sudden, the shocking occurs, our heads are wired to be in denial but eventually come to terms with that which changes irrevocably, and death is certainly in that category of things in desperate need of processing.

The flow of a Fijian funeral: Day 52

It didn't matter how many times people clarified the schedule for the funeral arrangements, they never began at the designated time. It wasn't about timing, though. It was about flow. Only when one group assembled could they continue with the next event, and with weather that echoed the widow's eyes, every moment was contingent on the skies. Being three foreign individuals unfamiliar with "the flow," we had to shuffle and scurry across the village to capture the sudden moments that would unfold in front of our eyes.

The funeral days commenced, and the village became a complete organism that moved in harmony with all elements. All we could do was observe and document.

My Bovine Faux Pas

The day Elias returned to the village, the clouds released their girdles and let it all hang out, much like the post-cyclone days of '09. The boys of the village prepared to help truck loads of relatives traverse Namado's cavern, which was slowly being covered with dirt in the first step of building the new bridge. I'm guessing this isn't often said: the Fijian government had good timing in starting this project.

I was rushed to the scene with camera in hand, having been told Elias was approaching and I needed to capture his coffin coming over the dirt bridge. The crowds coagulated on both sides. The dirt turned to mud. Insects feasted on our waterlogged feet. An hour passed, and the only news I heard hinted the truck carrying his body hadn't even made it past the first bridge on its inland journey.

Desperately grasping for timeliness rather than flow, I left the dripping spectators for my weekly call with home. I dangled my feet out of the doorway, phone to ear:

Mom, there is a cow staring at me right now. She's huge and black and standing in the rain. I think she's about to meet her maker. They already killed one cow today. I taped the whole thing. It was thoroughly disturbing.

...I think she knows I'm talking about her. She looks worried.

Having already witnessed one cow's demise that day, I couldn't have been paid to observe the second. Those twenty-five minutes of bone crunching and joint popping made me wonder, "When on Earth would I ever need all this raw footage of a cow slaughtering?"

The children crowded around the camera, one holding an umbrella to cover its weather-weary body and all filling my headphones with snickering and foreign whispers. I'm not sure what I was trying to accomplish by putting a wireless mic on a guy doing the killing. The sounds were beyond the worst from the Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

The most upsetting moment came a few hours later, when I was told to join Garrett in the community hall for a communal meal. As I stood at the threshold, slipping off my flip-flops, Garrett tried to get my attention and persuade me subtly to not enter the room. He knew I would have some hesitation with the meal of cow innards he was working on. Confused, I motioned I'd see what Jackie is doing, but the surrounding boys knew what I was trying to avoid.

We offended them. Abel came running outside to see why I didn't join them, and when he realized what Garrett had hinted, he was thoroughly ashamed. The stress on Abel's shoulders melted into his words, and I felt like the worst guest in the world. Our maneuver wasn't blatant, but the boys knew us well enough by then. I walked away crying, knowing I had let my hosts down in the worst way on the worst day for errors.

I'm no Bourdain or Zimmern. I am far from possessing a truly adventurous palate. To err in this way is among my biggest travel fears.

Elias' Last Hours in the Sun

The village illuminated the Highlands that night. Few eyes rested, as it is tradition to stay awake on the last night with the deceased. I was milked by the day and collapsed in my room to the sounds of singing and bugs buzzing around the lights, while the rest of the community continued to move their minds past shock to acceptance.

In the morning, Abel brought us to the hall again for a communal breakfast of tea and crackers. I sensed some action afoot, grabbed the camera, and poised myself outside the neighbor's house along with everyone else, just in time to see the casket emerged from its woven bamboo walls. Six of our friends hoisted it into the air, grabbing hold by the mat that cradled the entire vessel.

Stopping their procession in the middle of the village, the pallbearers lifted Elias above their heads, and his family and mourners began to bawl, passing under him in what was surely a monumental moment in the entire process.

Something caught in my throat, from behind the camera. I was witnessing a distant culture reveal itself in raw form. The ladies howled, hands atop their fluffed hair, and I shivered under the sweat coating my body. Wow.

The service was long, set to the sounds of belted harmony. A ribbon of people followed the casket from the church to the cemetery. Standing in a cathedral of leaves, we watched the widow and her eight children part with their father, many of their cries hitting high decibels.

Vittorina's body heaved and shook against my legs, as she stepped back and sat, watching her cousins, sons, and nephews lower her husband's body into the ground. Feeling her crouching frame against mine, it was unbearable to imagine the pain encapsulated within the adjacent skin. I cried for her pain, for the unfelt sorrow of her youngest children, and the next funeral I know I'd be soon attending.

And with that, it was over. People left the grave-peppered jungle floor to down more kava.

WARNING: Disturbing visuals of a cow slaughter from 1:39 - 2:15.

Any comments, questions, or anecdotes to share about any experience like this, your's or our's? Please let us know.

Hushed voices, broken bones, loud squeals: Day 51

I tried to clear it and ended up falling dramatically, my tumble only to be halted by Abel's quick save. My pants ripped, my clothes muddied, and my second toe folded in half under the weight of my falling body. It grew incredibly numb. I cursed the dark skies, but Abel's concern and kind words made me think, "I don't have to get pissed right now if I don't want to." I hobbled the rest of the day, in utter pain, but continued to smile.

When in Raki, dive like the locals dive: Day 31

I had never loved baked beans more than at breakfast that morning. Along with my scrambled eggs and tomatoes, everything tasted beyond satisfying. I was floating. I couldn't even eat the entire plate because my stomach had shrunk to the size of a guava. Ordering water, I received a sweating 1.5 liter of Fiji, no floaties, no mysterious colors, no hurricane residue. I sunk into the plush leather chair, admiring every smooth square inch, until we went for the beach.

The Final Shower

There aren't many things I regularly do on a trip. I don't always buy keychains or t-shirts to mark a new country or experience, and I'm hardly a superstitious person, with an arsenal of therapeutic exercises at the ready before each plane, train or automobile ride. I don't send postcards from every city, nor do I celebrate the end of a trip with a fancy dinner out. I don't do any of these things because I have a horrible memory and because one of the things I love about traveling is the weakened sense of obligation to do things that don't come natural.

However, there's one thing that happens at the culmination of every trip, and it happens as naturally as my leg hairs sprout.

I take a final shower, perfectly timed for cleanliness in transit, in sync with the rest of the last day's logistics, and completely akin to some sort of spiritual cleansing or washing of the slate clean. Each final shower marks a moment in my life no one else witnesses, but it holds some of the most intense feelings of the entire trip, all felt in a couple of steam-infused minutes.

My Fijian calling: rugby

In my 24 years, I have yet to learn or play rugby and have little knowledge of the game. My first game of touch was not to pretty. Actually, it was horrible. I have played a lot of soccer, so the running part wasn't a problem. It was the constant reverse passes and incredibly fast opponents. All the men are excellent athletes and put my lazy American butt to shame.

The addition and subtraction of lives: Day 46

It was odd seeing Garrett in such sour spirits on the road. The intense foot infection he contracted sapped him of his usual energy. I had no idea how to make him feel better. He needed a breather from the project and to relax in Suva for the days between doctor's visits, but meanwhile, the kids were looking forward to more innovation and games in the afternoons. I returned from our medical trip to Suva (where I learned I had at least two bacterial infections battling my body, as well), the same day we left the village, to a very empty house.

Feet Don't Fail Me Now: Day 43

This post was written by Garrett Russell. We rely on our bodies to work. That's a no-brainer. Traveling on a budget often involves staying in a hostel, taking public transportation, and very commonly using your appendages to get from place to place. I have walked all over this planet, and I expect my body to continue accommodating my knack for physical exertion.

But then I stepped on a nail.

The Ouchy Stuff

I thought I knew how to treat a wound. I've taken basic aid classes. I have a Bachelor's degree in Science. After stepping on the nail, I tried everything I knew possible to stop the impending infection. It probably didn’t help that I went swimming right afterward. I slapped a bandage on my foot and ran straight to the river. It was that hot.

The next day, my foot was not in good shape. I took some medication, tried to bear the pain, and hoped my body would handle the seemingly minor issue. Of course, Fiji isn't suburban America. I could never fully get clean in the Highlands.

The Fijians offered some interesting remedies, and even though I was skeptical, I gave them a try, for the sake of experiencing new methods. First, a boy named Cotu Cotu beat my foot with a stick to bleed out the wound - right after I removed the nail. Then Daiana, a woman of similar age to myself and Lindsay, placed my foot over a pot of boiling water with medicinal leaves. I gave in and allowed my foot to be scalded by steam for as long as possible. I was told to not walk on cement, because the wound would sense it and not heal. I was told to place as much pressure on the wound as I would normally, but as time went on, it was too painful to continue that route.

The Nurse Stuff

Obviously, the Fijian way of life is very different from our American ways. In the Highlands, if something doesn't concern someone, they don't find out (aside from the widespread frequency of gossip). And asking doesn't help either, because if there is no need to know, why ask? No one found it necessary to tell us there was a dispensary in the village, even after we asked about the nearest clinics. It wasn't until our little friend, Samu, showed up with a bandage on his leg that we knew we weren't the only ones with health supplies. We have been in the village for a month and a half, and we just found out what was potentially the most valuable resource we could have asked for regarding the project's success.

Vita managed the government-funded dispensary, meaning the government built a nice little house the size of an American bathroom and filled it with medical supplies we barely knew how to use. Having taken a few classes on first aid, Vita volunteered to be the one in charge, dedicated her time and her own money to make sure it was well-stocked and manned by someone savvy.

Hobbling over to the dispensary, we introduced ourselves to Vita and asked for some medical attention. She turned out to be the coolest women we'd met in the village, and we decided to give her all of our medical resources in order to train children and adults to find her for first aid.

The Undeniable Pain Stuff

The pain continued to escalate and was most bothersome when I tried to sleep. Not only was I sweating my you-know-what's off, but I was also fighting off mosquitos, lying on a hard floor, and trying to ignore the pulsing pain from my ever-swelling right foot.

Question: What do you do when you don't feel well?

Answer: Call your Mom.

I called her from the village phone, and with the use of Skype's awesome international rates, she gave me some comfort and valuable insight. I started taking Lindsay's antibiotics, but the bacteria traveled too deep into the soft tissue of my foot to be extracted. Since they didn't do the job 24 hours later, I had to go to Suva. As always, Mom knew best.

I found it ironic that I was in a village to teach people how to stay healthy, and I was the one that got a serious infection. Luckily, I knew when it was time to seek medical help, even when the villagers told me I'd be okay. Being the most savvy medical personnel in the village at the time, it was a big wake up call to realize I was the only one who could help myself.

The Doctor Stuff

The road to the village was still impassable over Namado, so at 5:30am, Lindsay and I walked the longest, darkest, most painful kilometer of my life. Wearing Crocs and using the side of my foot, I hobbled as fast as I could to reach the carrier on time. We parked in Suva at 10:30am, and the carrier was bound for the village three hours later. We booked it to the Suva Private Hospital.

With Lindsay on my arm, we flew via taxi to the medical center and, within twenty minutes, saw a doctor. Medications were prescribed, and for less then $25 USD, I was free to go - with one exception. The doctor asked me to stay in Suva for at least three days to make sure the infection did not spread or worsen.

Jackie was expected in three days, and Lindsay wanted to make sure everything was set in the village and that classes continued. For the first time on our trip, Lindsay and I parted ways.

The Suva Stuff

I sat in a coffee shop, searching frantically for a place to stay. My mind's monologue was endless. I was by myself, thousands of miles from home. I had an infection in my foot, and it was starting to travel up my leg. What if the medication didn't work? What if I have to have my leg removed? Would Fiji really be the place to seek medical help? Will my travel insurance cover amputations? Where can I stay that won't cost me an arm and a leg...

I found the South Seas Hotel for $7 USD a night. Though lacking in most creature comforts, I was happy to have the small bed and ceiling fan. I slept a lot. The infection completely wiped me out. I rested up, let myself heal, and prepare for our final month in the village and the arrival of Jackie, our first Nakavika Project participant. After almost two days, I could walk with a small limp, which allowed me to explore the capital city. I took in the epic cinematic masterpiece of Avatar - an interesting contrast to rural village life.

After those two days, I missed Lindsay, my foot improved - thanks to some Ciprofloxacin - and I was mobile enough to surprise our guest a day early at The Uprising.

The Practical Stuff

What would you do if your trip was interrupted by an injury? Do you have the knowledge to take care of yourself or your travel companion?

Here are a few tips that will help you prepare in case of an emergency.

- Travel Insurance. GET IT. Not only is it extensive, but it's reasonably priced. I recommend World Nomads.

- Be prepared. Know about the necessary immunizations for every destination but also think about bacterial infections. You may have a cut that never heals because of bacteria in the air, water, dirt, or inside your body. This is caused by poor hygiene (sometimes you can't help it), unclean water, and food.

- Bring enough or always have handy some sunscreen, aloe, band aids, antibacterial ointment, Pepto-Bismol, Immodium, and pain relievers. Water purification tablets aren't a bad idea either, and it's best to bring them from home to avoid the search abroad.

- Don't forget to hydrate! Drink water...'nuff said.

- Bring some supplements. I eat a terrible diet on a budget. In Europe, I went through one country on bread and Nutella.

- Notify the U.S. Embassy that you will be visiting their country. This will bring you up-to-date information about the country and provide valuable information in case of emergencies.

- Learn through IAMAT where the best and nearest traveler-friendly hospitals are in your destination countries.

httpvhd://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9P_2iuMDRHo

Have you had a similar occurrence on the road? A bad health problem you had to figure out or brave traditional remedies to try and fix? Share this post if you found it interesting or helpful, and comment your experiences/opinions below!

Independence in a Communal Society: Day 39

Returning after our holiday, we had not only our backpacks but boxes worth of books, school supplies, and ingredients for a week of comforting menu items. Fane gave us no hint as to when she would return to the village, and we were given permission to run her household to our liking, to cook and clean for ourselves. After being dependent on others for a month, we came back with something to prove to the village.

Making the Exotic Familiar

Ten days of tourist comfort reminded Garrett and me how much we yearned for the familiar: reasonably pure water, meals with lots of protein, comfort foods, and clothing that had even the slightest resemblance to clean. Instead of being reluctant to return to the adventure, we decided to find a new comfort with what Fiji provided; however, this also meant we took a turn for the debatably worse. Thankfully we didn't let the others closely witness the change, but we took it...there.

We became 'Mericans. Throwing our backs into the job of tidying the house, we scrubbed nature raw, paving paradise...in the 'Merican way. Taking the pure produce of the Highlands and frying it into submission, we cooked with Fijian ingredients...in the 'Merican way. Positioning our laptops near our work stations, we performed household duties while bouncing around in shorts listening to Lil' Wayne embrace obscenity...just like the 'Merican way prescribes.

Occasionally, we had a visiting mother come see what we were up to, curious as to why every piece of flatware spread across towels to dry in the hesitant breeze. The kids were ever-inquisitive, asking to play cards in our main room or shoot pool just to be in the presence of the beats. Most of the villagers found it surprising that we cared enough to scrub the walls and floors until the original colors were visible. It did seem a bit odd to make viciously clean what was nearly submerged in pure nature, but we were tired of being told not to do what seemed natural to us.

We wanted to feel comfortable, like ourselves, and because we had each other, we found an excuse to escape from the Fijian experience in our own American oasis.

Walking a Fragile Cultural Line

In the mornings, we were summoned by the neighbor children to come have breakfasts of scones, crackers, and tea. Though the fluffy scones in coconut cream were our favorite, we often wanted to experience our own breakfast routine (and infuse secret peanut butter into the menu).

Careful to not be offensive, we often explained that we'd already begun preparations of our own breakfasts of beans or oatmeal, sure to express our gratitude for the offer. The mothers always seemed pensive but understanding of our independence - we hoped our wild excitement for Fijian jobs well done would be endearing to them - but we soon felt them pull away and leave us alone for good.

Coming from a culture that encourages independence, we had trouble understanding why they didn't find our domestic attempts flattering. We mimicked their cleaning patterns and adopted the motherly civilities, like acknowledging everyone by name as they strolled by the house. The 'Merican oasis soon withered and became something akin to a typical household, as my sulu returned and Garrett took up manly duties.

When someone asked for help or a tool, we supplied them with what they wanted. And we continued to eat one or so meals a day at another person's house, in order to be social and imply our continued need and appreciation for their hospitality. We still had a desire to be a part of the communal atmosphere.

However, after a couple days of exercising our domestic capabilities, it felt as though we couldn't win both battles of comfort and acceptance. Our attempts to be comfortable while still submerged in another world were not universally well-received.

The Bi-Weekly Seminars

Even if our Martha Stewart tendencies didn't merit praise, we still thought our new adult classes would give us brownie points. We appointed Wednesday and Saturday nights as class nights, careful to swerve around rugby practices, processionals, committee meetings, and days when people typically went to the city.

That first Wednesday, we spread the word: Tonight is Q&A Night! We were teaching their children throughout those summer days, and yet most of the parents didn't really know why we were there or what topics we discussed. Additionally, people always seemed to have questions on health, hygiene, money management, and so on.

9pm came and went, and not one adult showed up, even after we confirmed the event with many of the main figureheads in the community. We sat in Fane's freshly cleaned common room, thumbing the little pieces of paper and freshly sharpened pencils we had prepared for the onslaught of questions and opinions. A couple friends stopped by to see what we were doing. "We're waiting for some of the adults to show for our Question and Answer session." The boys suggested we invite ourselves to a kava session, or we wouldn't be speaking to anyone that night.

The adults were busy with kava, as they were most nights. There was no special occasion, simply the occurrence of dusk. We became an afterthought, and though we knew no one meant offense by their absence, we couldn't help but take some. Sick of the grog and its apparently necessary presence at every social gathering, we were not about to speak over the din of a kava party about matters of health.

We went to bed defeated, hopeful for success next time, and comforted by a spoonful of peanut butter in a spotless room.

Urgency in health and a broken hip: Day 36

Even if the only information one is exposed to is from cable TV and the local newspaper, Americans know what makes them unhealthy, and many continue to live as though they don't. 34% of us are obese, so to travel globally and point fingers at people's awareness of their own health seems little hypocritical. However, these informational resources offer very current facts streaming in from the source of the new data. I don't think Garrett and I found a science or health book in the village that wasn't printed in the 1970s or a poster that wasn't peppered with indecipherable vocabulary from a medical dictionary.