Never have I felt so lucky to have this traveling job than I did on our attempt to summit Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, even in the face of extreme conditions and sudden danger. This is part 1 of a 3-part series on our journey to the top of Africa and a bittersweet goodbye four years in the making.

Basecamp

Shoving 100 wet wipes into a skinny bag with 3 liters of water, rain-proof pants, and the day’s lunch isn’t easy. Though my work “uniform” often calls for a back-bending pack of gear, I felt like a fumbling mess trying to make this little daypack of mine close. Tucked under the awning from the misty rain, I tried to pull myself together, baggage- and emotion-wise, to start mobilizing a group of teenagers toward a mountain.

Indiana does not typically breed the world’s most daring adventurers, and I never had realistic expectations of mountain climbing growing up; I think my hardest physical challenge from 3rd to 5th grade was trying to master the toe-touch jump. It never happened, well.. except maybe on a trampoline, but that doesn’t count.

These days my realistic expectations of daring feats have nothing to do with most people’s sense of reality. The realities of many of my friends and family back at “home” often involve children of their own, homeowner woes, and Disney cruises. It’s here, in this polar opposite work world of THINK Global School, that a late night email can inform me that I’m participating in a bucket list opportunity.

Ahh, the classic Kili spine twist. Breathe everybody! Breathe into the stretch!”

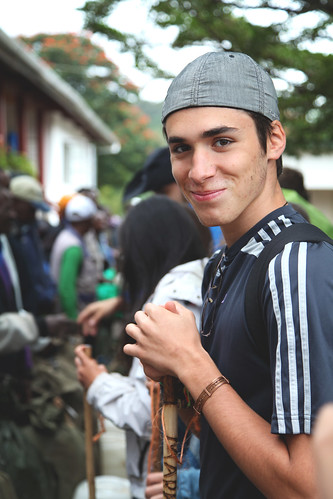

My technique as a supervisor of international adolescents is to make a fool of myself, and then somehow they listen to me, probably in pity. In the hours leading up to our ascent of Kilimanjaro, I pulled the kids into a circle to do some stretching. Behind us, somewhere past the mist and foliage, sat a gargantuan mountain that was going to drain us of our egos; sitting in her shadow, our circle felt miniscule in comparison, but we had to do something to calm our mounting nerves.

We stood back up from our stretches before the spitting rain could dampen the ground and our bums. Fifty-five Tanzanian men assembled into a line and stepped out to introduce themselves, followed by a quick utterance of "...morning." If they were apprehensive in the least, it was unbeknownst to us.

The porters–all local men from Moshi, topped with baseball caps and anchored with sneakers–were busy weighing bags and steel boxes of kitchen supplies, careful to limit their load to nothing greater than 20 kgs. Our climbing task seemed meager in comparison to their job of lugging our gear to high altitude. Feeling guilty for engaging in a task that required a personal porter, I was glad that I’d triple-checked my bag earlier for any superfluous items. My reverence for Clinton, my porter, grew ever greater on a daily basis; reverence that I tried to show with many double-handshakes through a debilitating language barrier.

I tossed on my tiny daypack and headed to the national park gate for registration and launching. Our assault on the summit was within sniffing distance, no longer a hypothetical challenge.

It was time to test a lot of things, most of which remained unknown.

Ascent

Within a minute of commencing the climb, I was glad I splurged on a rain hat. Those first four hours–the ones spent whistling and casually chatting–subjected us to unrelenting jungle rain, which showered us with water from unexpected places–dripping mosses high up in the trees and flicking ferns–as we forged onwards. For a time, I walked alone and excitedly wondered if anything in this African wild could kill me.

I could already feel my stomach respond to being 2,000 meters above sea level, and I craned my neck around every bend, yearning for a secluded spot to seek relief. The physical toll from the start had everything to do with the effects of high altitude: headaches, stomachaches, and other maladies ranging from the annoying to the life-threatening. My primary burden to bare was a stomach that couldn't lie. It felt like what it produces.

Throughout the forest and the moorland, I popped pills as nonchalantly as I would a handful of almonds. Downing so many pills certainly didn't feel healthy, but it was quite necessary to sustain myself. Regardless of water intake, I had a headache, reminding me of the magnitude of our challenge. Bush breaks were frequent, and thankfully I was with a few others in the back who wanted to walk together in peace and look out for each other whenever the wet wipes came unholstered.

Surprisingly, the walking was easy, always beautiful, and enjoyable. The air was delicious, the views serene and photogenic. My feet were thankfully blister-free, and all I could think of was:

Man, I'm glad I worked those fire escape stairs…

My training in our Hiroshima hotel had paid off. I felt capable of doing well as long as my body could stop reacting to the ever-increasing altitude and ever-decreasing oxygen supply.

On the evening of day two, against my strongest wishes, my head was throbbing. The lasagne on my plate seemed to be one unified consistency and without flavor to my compromised taste buds. Sadly, I had to retire early for the night, and I missed the view of a nearly-full moon floating above a cloud blanket below us. I spooned nightly with a hot water bottle, no name assigned.

Day three was prefaced as being “the disheartening day”–for the howling, cold winds and long stretches of land that seemingly never shorten–but I shared some lovely walking moments with many of my pals. We marveled together at the first unobscured sighting of our destination. We shared iPods and old favorite songs in the wasteland of the Kibo/Mawenzi saddle, the space between the two Kilimanjaro peaks. The students surprisingly went along with my self-absorbed renaming of Mawenzi to MaLindsay and referenced it with every glance eastward.

Many students refrained completely from technology or taking pictures, preferring instead to connect completely to the power of nature that surrounded them. It probably helped that they had two photographers trekking with them.

The ascent presented quite a few debilitating challenges–sun exposure, wind exposure, high altitude, blisters, dehydration–but their effects were hardly visible in these teens. I witnessed incredible grit in those fifteen [former] students, none of whom were weathered mountain climbers nor even teenagers who'd had adequate sleep for the two months prior. They looked out for each other and pushed through the monotony to savor the specialness of the opportunity.

Day three ended at the base of Kibo peak, and it was here where egos fell apart and fears became known. Continue reading with part 2.